Linneanism and systematics

The Haeckalian Bridge proposes that a cultural science would imitate biological science. However, cultural objects are sorely lacking any classification even approaching the sophisticated tools of biology. Hence then, a recapitulation of the taxonomic groundwork is much needed and Linnaeus’ systematics offers an initial candidate. This section will first consider the pre-Darwinian systematics that could not have foreseen evolutionary theory. It will then look at later forms of phylogenetics that incorporate descent with modification. Linnaeanism is first choice as it does not contaminate with a priori assumptions, leaving Cultural evolution theories independent.

Who was Linnaeus?

Wikipedia describes him and his work so clearly:

Carl Linnaeus was a Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, who formalised the modern system of naming organisms called binomial nomenclature. He is known by the epithet “father of modern taxonomy”. Many of his writings were in Latin, and his name is rendered in Latin as Carolus Linnæus (after 1761 Carolus a Linné). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Linnaeus The first edition of Systema Naturae was printed in the Netherlands in 1735. It was a twelve-page work. By the time it reached its 10th edition in 1758, it classified 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. People from all over the world sent their specimens to Linnaeus to be included. By the time he started work on the 12th edition, Linnaeus needed a new invention – the index card – to track classifications.

Because of his contribution to taxonomy, and his influence on evolutionary theory, the cross-application to taxonomising cultural objects may be suitably termed Cultural Linnaeanism.

The tools Linnaeus gave us

While Linnaeus might have classified a huge number of specimens himself, perhaps his greater contribution was in providing a system that biological taxonomists still use, and add to today. The Linnaean system provides some significant features.

Binomial nomenclature (or binomens) is the scientific name. This consists of two words in Latin: the first being the general class, while the second is specific. These two words then uniquely key a species. For example, opium lettuce Lactuca virosa; the genus is Lactura (having milky sap), the species is virosa – this is unrelated to the breadseed poppy Papaver somniferum and contains no opium. Common names for animals and plants are vernacular terms and vary from region to region and language to language. Furthermore, a vernacular name may not be unique, and two regions, or languages, might employ the same, or similar sounding name, to refer to completely different things. The vernacular might suffice for everyday usage, but a chaotic array of synonyms and homonyms are unworkable for scientific purposes. Precision requires a unique, unambiguous, and accepted reference among the community – one and only one name for each and every species. Of course, Latin is in keeping with scholarly tradition stemming from medieval schools and permeates medical and legal professions. However, as a dead language, it also opens up a kind of lingua franca, understandable from romance based living languages, but distinct enough not to be confused by the vernacular. Such binomens are globally accepted among the scientific community nowadays and has provision for introducing names for newly identified species, as well as resolving nomenclature clashes.

Another key component of Linnaean systematics is the ranking system. The binomens refers to the genus and species, but these are agglomerated into higher and higher classes whereby the levels are called ranks. While classification goes back at least as far as Plato and Aristotle, provided most of the ranks, the primary ones we now accepted (animals at least) as: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus and Species.

There are intermediate ranks between the major ones, and usually carry some prefix of a rank name “sub-“, “super-” “infra-” “parvo-” etc. eg. super-order. Botanical classification is slightly different, and viruses require their own method of classification altogether. Importantly though, Linnaeus’ system provides a divergent hierarchy which depicts the closeness of relationship between any identifiable specimens. As with the naming system, the organisation of ranks is extensible and self-correcting as it can be revised according to new discoveries.

What systematics shows

Let’s abstract the core principles as these will be considered later in relation to cultural taxonomy that also does not carry Darwinian inferences.

Each specimen requires unique and unambiguous identification, the equivalent of a primary key in data terms. This can be done with a numerical index, but it makes natural conversations about biota somewhat difficult, as scientists, as humans, prefer to talk with words that have some semantic coupling. Vernacular common names are neither unique nor universal. The binomial system, however, provides a special language that is easily identifiable as a scientific labelling system, that ensures a one-to-one relationship between the name and the species which are sufficiently meaningful to talk about and remember.

Systematics provides a divergent hierarchy of classes of biodiversity. It provides a catalogue of life, but more than that ordering and ranking gives us the relationships between classes, and in identifying a specimen we can find where it fits in with the rest of the biota. As an empirically constructed alpha-taxonomy, it depicts the natural pattern of relationships in the biota but is independent of any evolutionary inferences.

Both the naming and ordering schemas are consistant and can be extended where needed when a new species is discovered. The new species would then be related named and included into the existing structure according to a few protocols that are globally acceptance among the scientific community. Should conflicts arise, then these ground rules enable conflict resolution not only to the species but also to the structure of the ranking.

Influence on Darwin & Haeckel, Hennig, and the discovery of DNA.

Linnaeus’ system provided a divergent hierarchy whereby classes within classes show increasing sets of character similarity until those at the most derived ranks vary by few characters. Darwin’s Galapagos finches were mostly similar with variations in beak form from island to island.

Of Linnaeus’ work, Wikipedia says:

This was an influence on Darwin and his Theory of evolution by natural selection (1859) In 1854 he became a Fellow of the Linnean Society of London, gaining postal access to its library.[114] He began a major reassessment of his theory of species, and in November realised that divergence in the character of descendants could be explained by them becoming adapted to “diversified places in the economy of nature”.

Evolution by natural selection proceeds by speciation, the splitting by cladogenesis (clade Gk. branch), whereby descendants of a population maintain their form in the same environment, or maintain most of their form but with minor variation suited to their new environment. The genus then represents common traits (and so on up the ranks), while the species emerge owing to specific niche adaptations. Linnaeus’ alpha taxonomy, although it predates evolutionary theory, is of its divergent tree-like structure because of the ever splitting of species into new forms. Heackel’s tree-of-life illustrates his interpretation:

Later theoretical syntheses and discoveries such as Mendelian genetics, genes, chromosones, and the structure of DNA coroborate with a mechanical account of how such a tree structure could emerge. Given that Linnaean systematics can have Darwinian inferences, then this becomes an explanation for biodiversity. The alpha taxonomy is not a pattern of descent in itself, rather it is a clustering of traits. However Hennig, later recognised how to revise it as “geneological tree” like pattern that represented phylogeny and the ancestral relationships between extent and extinct species. This methodology is called cladistics (or phylogenic systematics), and its representation, a cladogram, depicts a pattern of descent that reflects Linnaus and Darwin.

Since the development of powerful number crunching technology, further iterations include phenetics (or numerical taxonomy) that codifies the traits of species and applies complex computational algorithms to produce clusteral hierarchy according to appearance. DNA sequencing, and efforts such as the Human Genome Project, are now allowing us to apply taxonomy to the molecular substrate.

Sytematics abstraction

Systematics is most mature in biology as that is where it originated, and suited to organising bio-diversity. But classification as we know from Aristotle, goes for all things. It can be seen, by abstraction, as an informatics concern: it is about information of things and mostly about morphology, or formal cause (morph=form). Systematics then provides a rule set, a methodology, a mathematical treatment, for the arrangement of an abstract class, and such a rule set can be re-instantiated in other specific domains. Of particular interest here is the application of systematics to the domain of cultural objects.

Recapitulating Cultural Linnaeanism across the isomorphic proposition

Respecification in the domain of culture

Culture is diverse. Some things appear to be more similar, and others more distant, and these can be ranked into a hierarchy according to that degree of similarity. Whiskey bottles on a bar-shelf bear some similarity of shape; they serve the same function, but brands will attempt to make their bottles distinctive to attract the customer’s attention. The same reasoning goes for coffee jars on a supermarket shelf, or packets of tea, or basically any goods. Clearly, the bottles and jars form a cluster, with the tea packets being an outgroup. We can go on clustering other such things as magazines, motor cars, feature films, battle ships and so on. This would give us an alpha-taxonomy, but there may be many variations depending on our clustering assumptions. Should we chose to depict our arrangements then we would have two trees, one of life and one of culture, but we can posit some kind of super-rank that encompases both trees of life and culture.

Evolutionary inferences are absent in alpha- taxonomy, as Linneaus was obviously oblivious to such in his time. This is important in the ontogeny of biolotical theory as the alpha-taxonomy does not carry any a priori assumptions of evolution, but needs an explanation for its structure nevertheless. If we did things the other way round and were to assume evolution in advance, then accordingly, we would inevitably find evolution in our constructions. An uncontaminated baseline avoids a circular argument but gives a grounding for further analysis that takes us through the the Darwinian, Mendalian, Huxlian etc.. stages and more sophisticated inference techniques.

Recapitulating development of evolutionary science with culture

In cultural evolution, we are at a point where we are contemplating evolutionary drives, but we do not know how or why, or for that matter, if culture does actually evolve. We do not have a solid taxonomy of cultural items that would be beneficial to a science of culture: one remains to be built. Of course, we are now aware of Darwin, and are tempted to leap to these evolutionary inferences, not bothering to recapituate the development of biological theory, and skipping the Linnaean stages.

A phylogenetic reconstruction of culture is commendable, and we might leap to phylogeny immediatly, in the light of Darwinian inferences, and gather the benefits of what it has done for biological taxonomy. But we are getting ahead of ourselves here, by not recapitulating the Linnaean effort. By going straight for the jugular, we are making the circular assumption in cultural evolution, that culture evolves. This assumption is unwarranted. In trying to establish that culture does evolve by cladogenesis, we will skew our findings whereby we cannot answer the foundational issue, and wo will descend into circular reasoning. We need to establish that culture does indeed evolve before reconstrucing the developmental path it takes. We need a base line, uncontaminated by assumption: a structure that needs some explans. Cultural Linneanism can be done in the absence of evolutionary thinking, and still produce a solid result. The Linnean stage then does not just give us a solid methodology and nomenclature, the real practial value in recapitulation is that it provides an uncontaminated alpha-taxonomy. Consequently, we need an analogue of the Linnaean stage before we can confidently move onto the Darwinian.

Notwithsanding the missing groundwork, we can still conjecture about the more advanced themes, realising that they are based on yet to be proven assumptions. Memetics and cultural engineering can still be done in practice much as human have used gravity long before Newton, E

instein or Bose. But without this acknowledgement, our acceptance is taken on ungrounded claims. With that caveat, we can still leap ahead to practice. It would still be beneficial to make a Cultural Linnaean effort sooner rather than later.

Cultural Linnaeanism’s benefits for Cultural Evolutionary theory

Cutural study lacks rigour, and I have suggested that CE would benefit, as an emerging science, from a solid taxonomic platform upon which we can understand the objects of our study. A cultural linnaeanism would provide such an uncontaminated basis, so given the benefits Linnaeus provided to biology, how might the attributes of his systematics be of benefit to a cultural science? The attributes of Linneanism were abstracted informatically earlier, they are made concrete for CE here.

Each cultural object or specimine (clion) requires unique and unambigous identification. Semantically loaded terms will aid conversation while some equivalent numeric index would assist numerical data manipulation. A latinesque binomial system would be distinct, meaingful, memorable, avoid vernacular confusion while preserving precision in talking about cultural phenomena.

A cataloge consisting of a divergent hierarchy of cultural classes would provide order and rank relationships. It would be a framework for identifying any cultural specimine to see where it fits in with the rest of the culture. As an emperically constructed alpha-taxonomy, it depicts the natural pattern of relationships among culture, but is independent of any a priori inferences concerning cultural evolution.

The shcemata for naming and ordering cultural objects would be consistant and extensible allowing naming and continuous addition of further cultural species. This culrual alpha-taxonomy would be self-correcting and conflict resolving and is offered as a lingua franca for the cultual evolution community theorists and practitioners.

So, given an solid system of understanding our basic objects of scrutiny, theorists would benefit by sharing some common assumption and definitions in what they are talking about. As with Darwin’s explanation of biodiversity, Cultural Linnaeanism would serve as a basis for establishing the presence of any pattern of cultural evolution, and the specific processes, for example in film adaptation, by which variation and selection takes place. As these patterns become better understood, then the agenda of cultural evolution research will become supported, including special interest groups such as archeologists, anthropologists, social psychologists, linguists, and so on.

But the instruments of Cultural Linneanism are not only academic; they are intended also for practical purposes. An acurately constructed picture of contemporary culture, of fasions, of trends, of products, supplies and demands, would assist decision support for those who are involved in planning and steering. Product designers, marketers, advertisers, politicians and policy makers, managers, and choice archetects of any kind, have an interest in forcasting their interventions. CL, and its subsequent uncoverings, combined with modern strategic information systems will translate into specific tools (predominantly software), so that those who shape our direction will have access to greater precision and hopefully better decisions, through a more solid system of understanding culture.

The methods of Cultual Linnaeanism

With this grand aspiration of charting the whole of cultural diversity, how might we draw specific methods across the Heakalian bridge and how might this inform a cliotechnology roadmap. The meta-methodology of proposing isomorphism and sculpting is employed whereby the specific aims are to perform the tasks and get similar results with culture that we do with biological patterns. In reality, the actual construction would involve a large data-set constructed by a community of researchers, which would then require specialist software to do the number crunching involved. The state of Cultural Evolution is nowhere near that point yet, but a mock-up can be sketched which illustrates the key points (Coubro & Lord, 2008).

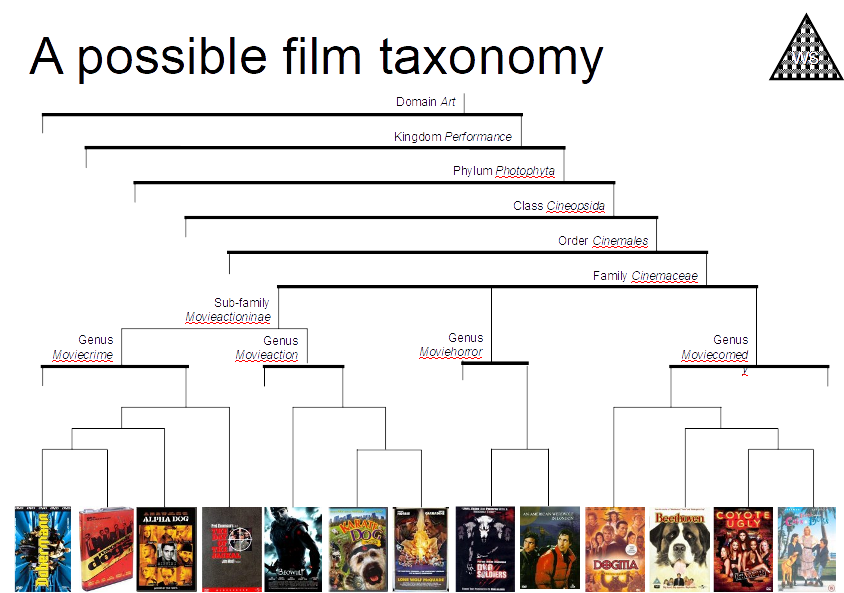

The mock-up tentetivly depicts a how a structure might look. It should be noted that the classification system was and still is incomplete as it should be constructed by consensus by a community of researchers. It shows a hierarchy of ranks with particular cultural objects (a cherry picked set of films) at the bottom as positioned with respect to a film genra. Owing to incompleteness in this example, the species (which could equate to either sub-genra or franchise) rank is not shown. The taxonomy shows some narrative cinematic releases, but could be extended to include other types such as documentaries, or instructional videos. A “dog” (maybe “toon”) Latin has been used playfully as a placeholder for naming taxonomic ranks showing how standard suffixes like “-aceae” could be used to denote the rank of family.

This proposed schema is not set in stone, and indeed might not be right. However, if there was any merit in it, then the details would need to be fleshed out. Are the ranks, the suffixes, and the toon Latin meaningful? It is anticipated that cultural researchers would argue and jostle the arrangement (for example about name bearing types) but eventually reach some consensus regarding the structure and the methods, thereby giving the system some stability. To repeat, the shema is intended to be agile such that it adapts to emerging knowlege rather than shoehorning the evidence to fit. Configuration management and version control (edition numbering) is advised.

Ideally, the cataloguing system would be complete before populating it with specific data for each clion (ie. cultural object) although version control would take care of any structural adaptations. For each unique species of clion then, a series of activities would be needed.

Firstly, the clion’s traits would have to be apprehended to ascertain whether it was a novel specimen, or something that had already been catalogued. Secondly, for a newly recognised species not already in the catalogue, then its relationship to existing species would have to be established so that it could be positioned in the taxonomy. Thirdly, some consistant nomenclature would need to be proposed in parallel to binomial nomenclature. Perhaps it would be included in an existing genus, or perhaps it might be entirely new whereupon proposals for new higher ranks would be welcome.

As the catalogue builds, then further inferences (shown later) can be drawn regarding properties like synapomorphies and mechanisms of inheritance.

Practicalities and problems to solve

The method described above would be necessary to construct a Cultural Linnaean alpha-taxonomy. But there are some practicalities to consider: mainly that it is something of a Trojan task and that we currently do not have the dedicated tools. Given the state of play of technology and the maturity of biological taxonomy, then such problems are not insummoutable; they are mostly implementation details.

Linneaus obviously did not have the benefit of modern computer technology, but his work shows us that the task of cataloging culture is of epic proportions, perhaps even bigger than that of biology. Biological taxonomy, genetic databases, and especially numerical taxonomy were unfeasable before the information revolution. Nowadays, access to catalogues and globally collaborative projects can be done just about anywhere with a wifi connection.

Software and the web, therefore are the key to enabling a Cultural Linneanism. They allow mass contributions, and access from anywhere in the world.

Practically then, the systematics should be reflected in a data structue, which at its core, would be a tree. As this structure is likely to change, along with updates to the actual clia data, then strong configuration management and version control (CMVC) is essential. This is not just about software updates, CMVC is the very essence of evolution and so should be mirrored in a model that considers evolution.

As the ultimate aspiration is to catalogue each and every past, present and emerging clion, then the effort is clearly beyond that of a single individual. Mass collaborationn is envisaged, using web based interfaces and tools, such as a wiki, that allow geolocation independent crowd sourced contributions.

Inferences: gaps in map for cultural engineering

The true reward comes from the inferences that will emerge from the data. What kind of things would a Cultural Linnean system open up? The academic use in working out how culture evolved has been discussed, but the exciting cliological prospects are those that would come from futureology and practical cultural engineering.

The immediate benefit would be a kind of orienting. With some map of past and contemporary culture then we can get a better picture of the state of play. We can know where we are.

Given our current predicament, and the dynamics, then we can have a go at forcasting future events and developments. What is likely to become popular, what is likely to adapt, whatis likely to fade into obscurity. Like weather forcasting cliology can only hint at the prospects, providing an educated guess at best. The further into the future we try to prophesise, the more accuracy we lose.

Like it or not, we are all active agents in cultural development, and have an interest in influencing how the future is shaped. If we can forcast the implications of our actions, then we can select our actions according to our intentions. Politely put, cliology offers a tool for decision support, the navigation and steering of the course of future history. Cybernetics, originally came from the principle of “steering”. Hence, as a tool, cliology offers a tool for knowing where we are, where we want to be, how to get there, and how to adjust if we get off course. A Cultural Linneanism indicates the gaps-in-the-map, novel suvival strategems and structures, eka-clia, that might not otherwise be expored by persueing the current direction of cuture and technology. By showing us where they are then we can evaluate whether they might be more beneficial than following the prevailing course. Many of the potential combinations are likely to be inviable, but the capacity to envisage the metaphorical lay-of-the-land might reveal the existance of a Shangri-La, cut off from the outside by impenitrable mountains. Futher, it may also expose the secret passes by which to get there.

By way of example, we might consider research, development and marketing of a new product. We would know then what exists in the market already, what is missing, what is likely to be useful and popular, what we need to know to produce that item, and how to ensure it maintains relevancy as preferences shift, and competition adjusts. We could go futher, PR wise, and influence those preferences in advance.

Now what?

We have seen, in the advent of AI, the classification and analysis of biological species by computer software, databases, and networking. Current development should see the translation of these tools for similar applications in the cultural application: a data schema that supports a vast crowd sourced data-set across the network. Models for capturing memes are under construction (TRIPWIRE) which inform the specifications for software development such as Cliobase (an on-line catalogue of cultural objects featuring strong version control), and MENDEL (clustering software that constructs phenetic relations and tracks inheritance among clia).

Once these bases are available, then software tools for garnering inferences, forcasts, and decision support should be within reach. These will feature visualisation systems, such as strategic fittness landscapes, that help researchers, policy makers, and choice archetects apprehend and select from the options. Such software systems will have the capability of recombining meme fragments, assessing their simulated danqness (EDEN-ML), releasing them into culture across vectors, and tracking their effectiveness in inducing cultural change.

As for far future development, we turn to a more speculative science fiction. We need to dream about AI and a massivly connected world. One where futureology steers the direction of futurology itself. We need to turn to the likes of Asimov and Flynn to see the promises and dangers of where all this might lead.